Quantum Computing & Grover's Algorithm

So far, we’ve talked about Shor’s algorithm, which cracks tough problems like factoring and the discrete logarithm problem by exploiting hidden periodic structures. But what if your problem really is just “finding a needle in a haystack,” with no obvious underlying pattern to latch onto? In other words, what if you need to search through an unstructured list of possibilities to find the one correct answer?

Classically, this is as bad as it sounds: if you have possibilities, you might have to check them one by one, taking steps on average. Grover’s algorithm, can solve this kind of “unstructured search” in steps. That’s not the superpolynomial speedup you get with Shor’s algorithm, but it’s still an enormous gain when is large. After all, the square root of a huge number is significantly smaller than the number itself.

Just like with Shor’s algorithm, let’s get one misunderstanding out of the way. Grover’s algorithm doesn’t let you magically solve all search problems instantly. You don’t just prepare a superposition of all items and measure to get the solution. If you tried that, you’d just get a random guess — effectively useless. Instead, Grover’s algorithm cleverly uses quantum superposition and interference to “amplify” the correct solution, making it stand out from the crowd.

You still have to perform a sequence of well-chosen quantum operations. The difference is that now, there’s no hidden periodicity to exploit as in Shor’s approach. Instead, Grover’s algorithm systematically rotates the quantum state in such a way that, after about iterations, the right answer pops out with high probability.

Imagine you have a database of items, labeled from to . Among these items, exactly one is marked as the “target.” Classically, you’d have to check each item to see if it’s the target, and on average you’d find it after checks, which is complexity.

A quantum computer, by contrast, starts with a superposition of all items:

This state says: “the answer is equally likely to be any of the items.” But that alone doesn’t help you. Just measuring now would yield a random item. You need a way to “steer” this superposition toward the correct answer.

Grover’s algorithm requires an oracle, a special quantum subroutine that can “check” if a given item is the target. In practical terms, it means you must encode the property of “being the correct solution” into a quantum operation that can flip the phase of the target state. This oracle is like a quantum black box: you feed it a state , and it tells you “target or not” by changing a sign in a subtle quantum way.

If the item is not the target, you do nothing special. If it is the target, the oracle flips the amplitude’s sign. Mathematically, this looks like:

This phase flip might seem like a small, insignificant change, but it’s the key to letting interference do its job.

Once you have the oracle, Grover’s algorithm applies a sequence of steps often called “Grover iterations.” Each iteration does two main things:

Step 1 - Phase Flip with the Oracle: You apply the oracle to the current superposition. This changes the sign of the amplitude associated with the target state, leaving all other states unchanged.

Step 2 - Invert About the Mean (Diffusion Step): Next, you perform a “diffusion” or “inversion about the average” step. This operation effectively takes the new amplitudes and reflects them about their average value. You can think of this as a geometric transformation on the amplitudes, pulling the target state’s amplitude upward while pushing the others downward.

The combination of these two steps is critical. Initially, all states have equal amplitude. After one iteration, the target state’s amplitude becomes slightly larger in magnitude than the others. After two iterations, it grows a bit more. With each Grover iteration, the amplitude of the correct solution gets steadily “amplified,” while the others get diminished.

What’s really going on is quantum interference at work, just like in Shor’s and other quantum algorithms. But now, instead of singling out a periodicity, you’re leveraging interference to increase the probability of measuring the target. The oracle’s phase flip introduces a subtle asymmetry into the superposition. The diffusion step then magnifies this asymmetry, causing constructive interference for the target and destructive interference for the rest.

The math behind this is neat but intricate. In the end, Grover’s algorithm finds the target in queries to the oracle. Compared to the classical , that’s a substantial improvement. For very large , is vastly smaller than .

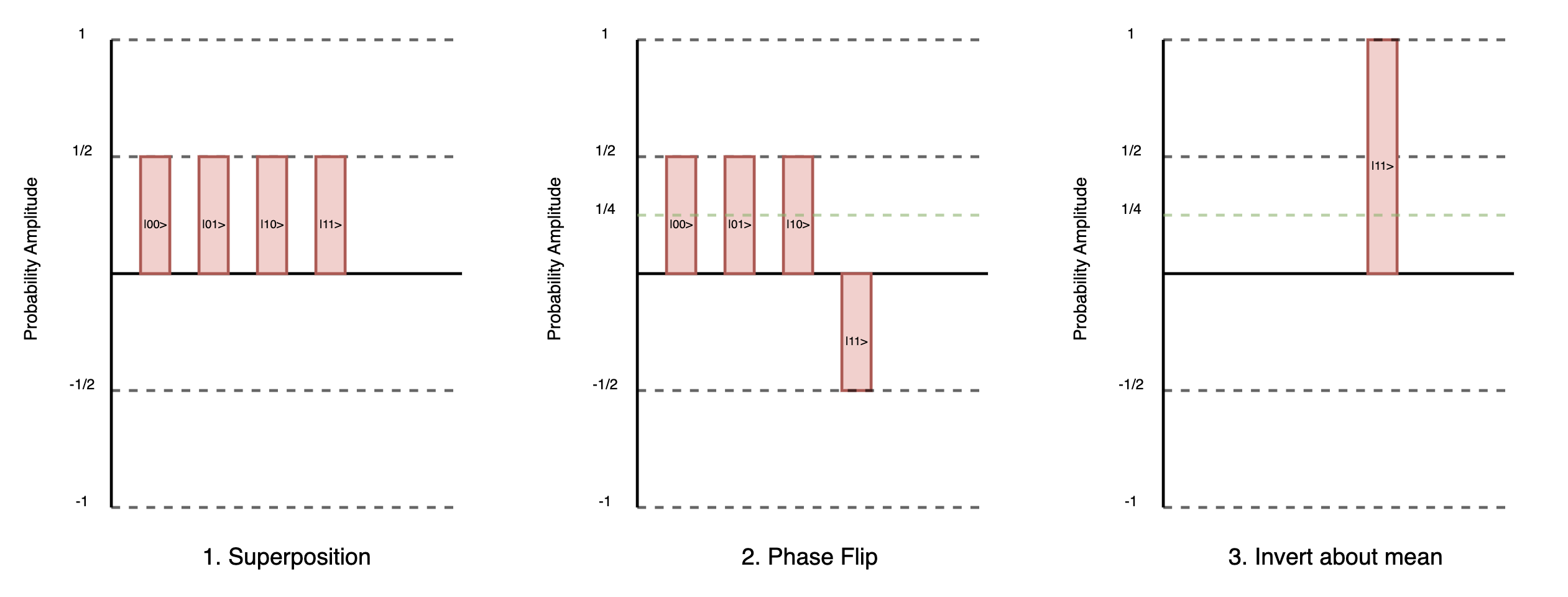

If you’re a visual learner, below is a visual representation of Grover’s algorithm with each step explained. Note, to make it easier to visualize we will use only 2 qubits i.e a search space where . We will pick the state as the target state.

Grover's Algorithm

Step 1 - Superposition: After putting the quantum state into superposition all possible states , , , and are equally likely to be chosen as our “answer” - this effectively leads to a random guess, not very helpful. Formally, each state has an amplitude of , given the probability of a state being measured is it’s amplitude squared, each state has an equal probability of being measured ().

Grover's Algorithm

Step 1 - Superposition: After putting the quantum state into superposition all possible states , , , and are equally likely to be chosen as our “answer” - this effectively leads to a random guess, not very helpful. Formally, each state has an amplitude of , given the probability of a state being measured is it’s amplitude squared, each state has an equal probability of being measured ().

Step 2 - Phase Flip: We mark the correct answer by flipping it’s phase. This is the subtle asymmetry we are looking for. Now 3 of our states have an amplitude of and the “target” state has an amplitude of . This has done nothing to help us measure the correct answer as each state still has the same probability of being measured.

Step 3 - Inversion about the mean: The diffusion operation (inversion about the mean) reflects each amplitude about this average. Mathematically, if the old amplitude is and the average amplitude is m, then the new amplitude is given by: .

is easy to visualise in the image above. We simply sum all of the amplitudes and then divide by the total number of states. Sum of amplitudes:

Thus

Applying this to each amplitude, for the “incorrect” states , , and :

For the “correct target state” :

In other words, after the diffusion step, the entire amplitude is now concentrated on the marked state . This is exactly the outcome Grover’s algorithm aims for: the probability of measuring the marked state is now 100%.

Just as with Shor’s algorithm, implementing Grover’s algorithm isn’t trivial. You need a fault-tolerant quantum computer with enough qubits to store your entire search space in superposition and to implement the oracle. And remember: you must know how to construct that oracle! If the oracle itself requires work to build, then the advantage can fade.

Nevertheless, Grover’s algorithm has broad conceptual significance. It proves that quantum computers can speed up the solving of “needle-in-a-haystack” problems. While the speedup is “only” quadratic, it’s a fundamental result showing that quantum computation can improve brute-force search tasks — not by a mere constant factor, but by a scaling improvement.

Some cryptographic systems that rely on large key sizes to protect against brute force attacks might be impacted. They’d need to at least double their key lengths to regain the same security margin against a quantum attacker using Grover’s algorithm. For example, a key length of bits that required classical attempts would only need attempts with Grover. This means doubling would restore the original difficulty level.

Grover’s algorithm stands as a cornerstone in the quantum algorithmic landscape. It doesn’t rely on hidden periodicities or group structures the way Shor’s does. Instead, it cleverly enhances a brute-force search using superposition and interference. By iteratively “rotating” the state toward the solution, Grover’s algorithm shows us a different side of quantum computation: one where we can still leverage parallelism and interference even without a richly structured number-theoretic problem.

In short, Grover’s algorithm is a powerful reminder that quantum computing can help in a wide range of scenarios, not just factoring or discrete logs. It’s a demonstration that when you trade in classical certainty for quantum uncertainty — and then cleverly harness that uncertainty — you can bend the scaling laws of computation to your advantage.